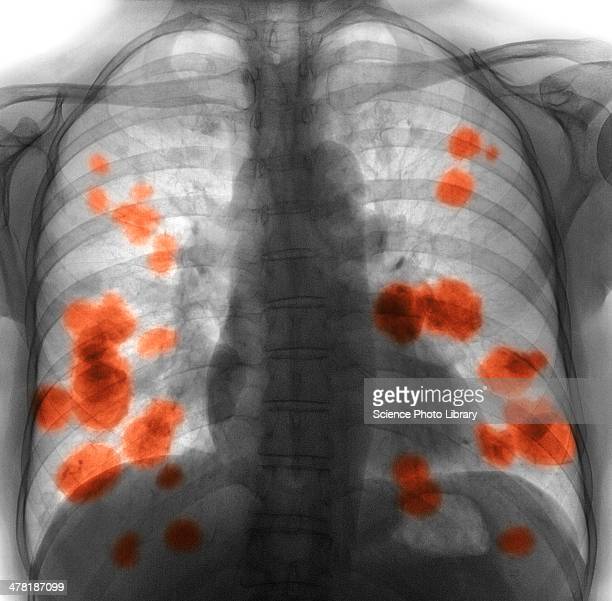

Secondary lung cancer. Coloured X-ray of the chest of a 52 year old female patient with metastatic (secondary) lung cancer (red).

There have been over 60 attacks on health facilities since the start of the war in Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine risks disrupting hundreds of clinical trials taking place in Ukraine and Russia. Swiss pharmaceutical companies are directly impacted. This not only leaves patients without access to treatment but threatens the development of promising new drugs.

When Incyte’s Chief Medical Officer Steven Stein learned of the invasion of Ukraine, he immediately thought of the people involved in the company’s clinical trials. The US biotech company, with European headquarters in Switzerland, works with ten third-party contractors in Ukraine who do site and data management. As of last week, 78 people in Ukraine were still receiving treatment as part of their trials.

“When the war started, our philosophy as a company was – this is about continuity of care for patients. That’s it,” Stein, who is responsible for Incyte’s clinical development plans, told SWI swissinfo.ch. “These people are already very brave. They have cancer and they’ve already volunteered to be in the study. What we’ve said to them is that we’re going to do everything for you to continue getting care.”

How do clinical trials work?

But continuing to provide treatments and maintain strict clinical trial protocols as hospitals are bombed, millions flee the country, and cancer patients shelter in bunkers is daunting. Incyte confirmed that all of their contract colleagues are safe in Ukraine or neighbouring countries. And, while their trials have been disrupted, they are working with local medical professionals to ensure continuity of care for patients and maintain the integrity of the clinical trials.

If the war continues, the consequences will not only be devastating for patients enrolled in trials in Ukraine, many of whom saw a trial as their last hope. It also risks halting progress on many promising cancer treatments – many of which are being developed by pharmaceutical companies in Switzerland.

Why Ukraine?

Incyte is one of many pharma and biotech companies that have been setting up trials in Ukraine in the last decade. According to an investigative reportExternal link by the NGO Public Eye, published in 2013, Ukraine started to become an attractive place for companies to locate global clinical trials starting in 1996. Lower costs and legislative changes to bring clinical trial practice in line with international standards led to a rapid rise in trials set up in the country.

The healthcare system is also good, says Stein. “There are very good hospitals, imaging facilities and very good doctors.” The country also has a solid reputation for enrolling patients quickly and producing reliable data.

Mihai Manolache is CEO of Cebis, a Swiss clinical research organisation based in Lugano that sets up and monitors trials for pharmaceutical clients. He told SWI that there is also a large treatment-naïve population, which means there are many people who haven’t had any treatment for a disease and therefore, make good subjects for a study.

Swiss companies are distancing themselves from Russia following the deadly attacks on Ukraine and subsequent economic sanctions.

Ukraine is also an increasingly attractive market for companies. “It’s not part of the European Union, but it is the largest country in Europe with 40 million people,” said Manolache, whose company has conducted trials in Ukraine in the past. “Clinical trials are one way to get a foot into the market.” Switzerland’s largest exports to Ukraine and Russia are pharmaceutical products.

Incyte, which has about 2,400 employees, runs about 140 clinical studies globally at any one time. While three trials in Ukraine seems like a small number, in a major trial for its investigational PD-1 monoclonal antibody to treat lung cancerExternal link – around 30% (160 out of 530) of the patients who have been enrolled in the trial since it started were in Ukraine.

Basel-based Roche has more trials in Ukraine than any other pharmaceutical firm, according to the United States Food and Drug Administration Clinical Trials registry. Around 20% of Roche-sponsored trials have sites in Ukraine. The average for the whole industry is 4%.

Some are for key drugs for cancer and neurological diseases. For example, more than half (8 out of 16 active or recruiting of global trials) of the trials for its recently launched drug – Ocrevus to treat multiple sclerosis – have at least one site in Ukraine. There are 18 active or recruiting trials in Ukraine for Tecentriq, which was approved by the FDA for certain lung cancers last year.

In a statement, the company said that Ukrainian patients represent about 1.5% of the active patient population across its global clinical trials. However, there is no data available on the share of Ukrainian patients in individual trials.

What today’s war means for tomorrow

As the war continues, there’s growing anxiety and uncertainty among pharmaceutical companies about the future of many of their trials and the patients involved.

The war is threatening medical supplies and making it harder to keep and track health records not to mention the personal safety concerns for patients and physicians. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported on March 24 that there have been 64 attacks on health facilitiesExternal link since the start of the war.

Roche has set up a task force to monitor the situation and created a hotline for patients to call for information and support. The company has donated medical supplies, including antibiotics, reagents, and specialised medicines for treating influenza, rheumatoid arthritis, and various cancers.

In an emailed statement sent to SWI, a Roche spokesperson said the company is “actively working on solutions to ensure continued access to treatment for these patients, including if they have left Ukraine and moved to other countries”. He added that a number of neighbouring countries have confirmed displaced persons or refugees “will be eligible for the same access to healthcare as local citizens”.

But this isn’t always straight forward. In an interview in the science and technology magazine Wired UK, Ivan Vyshnyvetskyy, president of the Ukrainian Association for Clinical Research, said that “it is almost impossible to ship biosamples [blood, plasma, etc] from Ukraine and investigational medical products into Ukraine from the sponsors”. Many of the materials required for clinical trials are located in Kyiv, which is a combat zone, he said.

One physician in Ukraine involved in one of Incyte’s clinical trials voluntarily went to the border to pick up a drug and bring it back to a site so that a person could continue receiving treatment. Media reports have captured similar harrowing stories of medical professionals going to great lengths for a patient to stay on a treatment.

With the war still raging and millions seeking safety, it’s difficult to estimate the long-term impacts on drug development. Most drugs take more than a decade to develop, and in some cases, a single phase of a trial can last four to five years. Most of the trials in Ukraine that are sponsored by pharmaceutical companies are global trials, and therefore, enroll patients at multiple sites in several countries.

Why Switzerland matters for the tropical forests

While there is this deep-rooted tradition of respect of the environment in Switzerland it does not necessarily extend beyond the country’s borders.

Stein said that many of the digital systems and tools set up during the Covid-19 pandemic are helping Incyte stay connected with patients and physicians. The pandemic interrupted many clinical trials when people couldn’t go to the hospital for treatment. As a result, agencies like the FDA established statistical methods to deal with missing data.

This is the story of how making drugs helped turn a small, mountainous country into an industry titan, and what the pandemic means for its future.

Roche didn’t respond to SWI queries about whether any sites in Ukraine have been withdrawn from trials or any patients have been replaced. However, Reuters said on March 11 that at least seven companies had reported disruptionsExternal link to trials in the country.

Stein told SWI that while Incyte is doing everything it can to ensure patients get access to treatments, if they lose contact with patients, they will have to replace them on studies.

“This would happen if, for example, there was a complete Russian takeover of a city or sites and it became impossible to interact with the site and connect with patients electronically,” Stein told SWI. “This is painful on many levels.”

Ethical dilemmas

Most of the big pharmaceutical companies also sponsor clinical trials in Russia; these face an uncertain future too. Some 38% of Roche-sponsored trials have at least one site in Russia. At least six trials for Roche’s highly-anticipated Alzheimer’s drug Gantenerumab, which is expected to launch later this year, are in Russia. Novartis has only a few sites in Ukraine, but 26% of its global trials have a site in Russia according to the FDA registry.

While medicine is exempt from sanctions, many company-sponsored trials are indirectly impacted because the trials are financed through accounts in Russia state-owned banks. Incyte has about 26 patients enrolled in a handful of trials in Russia. “A big issue is the financial part. How are we going to pay those sites for the work they do, given all the sanctions,” Stein told SWI.

Several companies have already said they are pausing new trials in the country. On March 22, Novartis released a statement saying that in addition to suspending capital investments, media advertising, and other promotional activities in Russia, they aren’t setting up new clinical trials and are pausing the enrollment of new study participants in existing trials.

Roche is also putting new sites and patient enrollment on hold in Russia. “Our priority remains to ensure that all patients currently enrolled in clinical trials in Russia continue to get access to treatments,” a spokesperson wrote.

While Stein says Incyte typically allows individual sites to decide whether to continue with sponsored trials, he told SWI that “at this juncture, we are unlikely to encourage more enrollment in Russia”.

Ukraine’s top government officials have accused the Swiss multinational of being complicit in Russia’s “war crimes” in their country.

Sanctions aside, the companies also face moral dilemmas about whether to continue working in Russia at all. In early March, Vyshnyvetskyy published a letter on LinkedIn on behalf of the Ukrainian Association for Clinical Research calling any companies that continue to operate in Russia “unethical and shameful”. More than 800 company CEOs, executives and investors have signed an open letter urging pharmaceutical companies to stop doing business with Russian industry. It stopped short of calling for companies to stop supplying medical goods, but some global companies have already said they are restricting shipments to “essential medicines”.

Roche has remained steadfast in its response to pressure. Roche CEO Severin Schwan told the German-language paper Tages-Anzeiger on March 29, that they have a responsibilityExternal link to all patients who depend on their medicines. “We can’t just withhold life-saving cancer drugs from Russian patients,” he declared.

纸飞机中文版 群组功能强大,可容纳大量成员,适合社群交流和信息分享。

访问telegram,探索其丰富的功能,包括群组、频道、Bot和自定义贴纸。体验更灵活的沟通方式。